It has come to my attention that my 2010 article about ceramic artist Dorothy Kindell has disappeared into the slipstream of the ever-ephemeral interwebs, not unlike the subject of the article itself. So I figured I’d stash it here, for safe keeping. (Please excuse any wonkyness or weird typos.)

IN WHICH JANE WIEDLIN AND I SEARCH FOR A FORGOTTEN NAKED-LADY MAKER

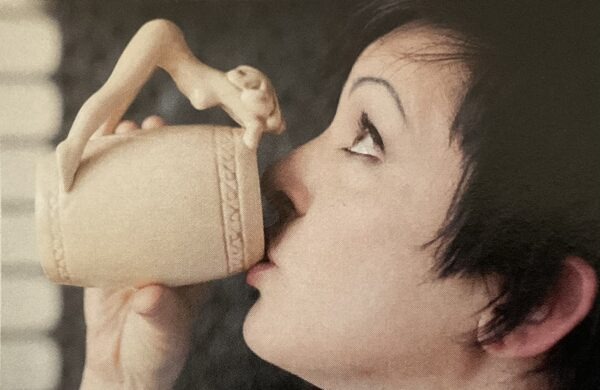

I was at a cocktail party in a downtown loft hosted by my friend Jane Wiedlin when I saw it. There on a shelf was a simple barrel-shaped mug with a peachy beige glaze. What caught my eye was the handle–a nude female figure, bent over, back arched, legs open, hands buried in a wild, curly spill of hair that obscured her face. Her body language was nothing like the calculated come-hither of a professional model or a burlesque queen. She seemed utterly unselfconscious, as if caught in a moment of private, primal ecstasy. There was something graceful, fluid, and intensely feminine about her pose, as if it were intended not just to titillate but to celebrate the natural beauty of the female form.

“Look at how streamlined the figure is,” Jane said. “You can practically see the woman moving. That’s a Dorothy Kindell.”

Best known as a singer and songwriter for the Go-Go’s, Jane has been collecting midcentury lowbrow girlie art for years, which makes sense. If anyone was going to have a cache of naughty ’50s barware cartoony caricatures of female sexuality known as “Nudie Cuties”- it would be Jane. While she and I have been friends for nearly a decade, we had never talked about her Dorothy Kindell fixation. Jane told me she’d been a fan of the potter since the mid-’90s, when she found a set of six mugs on eBay that depicted a woman stripping. The vessels were “progressive,” in that the figure started off clothed in the first and ended up naked in the last, tumbling headfirst into the cup. The seller described the items as “looking like a Dorothy Kindell set.” Jane, who considered herself pretty knowledgeable about the genre, hadn’t heard of Kindell. “I immediately became obsessed,” she told me. Soon, I would be obsessed, too.

I write for money – hardboiled crime fiction but also novelizations of popular movies like Snakes on a Plane. Even before I began doing that for a living, though, I believed in the significance of throwaway pop culture. If you ask me, to understand the zeitgeist of an era, you shouldn’t bother analyzing highbrow art and the self-important stylings of literary masters. Check out the cheap stuff. The kitsch. The quick-and-dirty dime novels, the trashy vintage paperbacks. Because in the process of trying to pay the bills, pulp writers and artists often tell it like it is. Their deadlines don’t give them time for a lot of phony posturing, and as a result, their work tends to reflect how people really are rather than how they want to be perceived.

Much of my work falls into this category. So does Jane’s. To us, just because something is commercial doesn’t mean it can’t be artistic.

Both of us have challenged traditional assessments of who can work in particular mediums. Jane was one of the first self-made female rockstars. Unlike many earlier iconic girl groups, who sang songs written by men and were backed up by male musicians, the Go-Go’s wrote every one of their chart-topping hits.

Similarly, I’ve tried in my fiction to take the standard clichés of tough guys and femmes fatales and turn them inside out. My heroine is Angel Dare, a former porn star who, after being raped and left for dead, goes on a quest for vengeance against the men who hurt her. Far from some kick-ass male fantasy, she’s a realistic, middle-aged woman with flaws and strengths who fights back the only way she knows how.

I guess what I’m saying is that long before Jane introduced me to Dorothy Kindell, the stage was set for me to love her. Getting to know her, however, would prove more difficult. Few of the vendors who sold her work seemed to know much about her, other than that she’d lived and worked in Laguna Beach in the 1940s and 50s producing what is known as “art ware”: decorative collectible figures, including exotic dancers and sexy naked women like the ones in Jane’s collection. As I browsed the images, I noticed that Kindell’s most alluring nudes all had their faces hidden. Just as the artist herself remained hidden from casual inquiry.

Other projects came and went, but I couldn’t get Kindell out of my mind. Jane and I talked about her a lot. Our discussions veered from art and sexuality to mortality and leaving a legacy. Who was this woman who created such erotically charged figures during a time when women were primarily homemakers, actively discouraged from exploring their sexuality? Why had she been largely forgotten? It was Jane’s idea to try to find out.

Robin Donner is the founder and administrator of the Web site DorothyKindell.com. He learned of Kindell from his wife, who discovered her in the mid-’90s. But it wasn’t until he acquired his first Kindells, a pair of Balinese dancer lamps, that Donner became smitten. “Her pieces are unique, high quality, and often whimsical” he told me. “They are also not abundant, which makes collecting her work a fun challenge.” His collection includes nearly 200 Kindell pieces. He has six favorites: a sequential set of mugs that depicts, in Donner’s words, “an American soldier stationed in France after the war hooking up with a lady of the evening and then dodging the police.” It is worth as much as $1,300. Donner confessed that he knew little about the woman behind the ceramic babes, but he wanted to help. He sent Jane and me xeroxed copies of some ads for Kindell’s work, which winkingly described her figures as having “eye appeal.”

A 1956 ad was for a six-piece stripper set like the one that had seduced Jane. Each cup in the “action parade,” as the ad called it, had a name: Invitation. Fascination. Agitation. Meditation. Exhilaration. Intoxication. “They sell on sight!” the ad read. A 1951 ad for “The Beachcombers,” an ashtray featuring two pairs of nude legs sticking out from under an over-size sombrero, read: “Remember, in ceramics…if it has ‘Eye Appeal,’ it’s from Dorothy Kindell.” The most surprising detail? These ads were not featured in men’s magazines. They appeared in ordinary design catalogs and home decorating journals alongside unremarkable vases and ashtrays. In other words, they were aimed not at fine-art collectors but at housewives looking for something fun and frivolous for the knickknack shelf. The ads were enlightening, but they weren’t much to go on. Then Donner mentioned that Kindell had two daughters, both in their eighties. Rumor had it that they were “very secretive,” he said. He did not know how to contact either one.

My next stop was Bill Stern, the author of California Pottery: From Missions to Modernism and executive director of the Museum of California Design, “Kindell developed an industry-wide reputation for her distinctive, irreverent figural ceramics,” he explained, Her dancers were unlike the fine-art nudes of Beatrice Wood. Her playful barware had nothing in common with the practical cups and dishes by Edith Heath. Some male artists in Laguna Beach produced the occasional topless hula girl, but their pieces lacked the fierce sensuality of Kindell’s. Like Donner, Stern could tell us next to nothing about Kindell’s life. But he did possess one piece of the puzzle, the address of her original Laguna Beach studio: 1920 South Coast Highway.

I drove. Jane rode shotgun.Big band swing burbled from the radio as we speculated about what sort of revelations might await us. What sort of person would Kindell turn out to be? A rebel flying in the face of the June Cleaver standard for appropriate female conduct? A seemingly meek conformist living out her fantasies through her artwork? An unapologetic protofeminist pioneer?

“Best-case scenario?” Jane said. “We find someone who actually knew her, someone with a personal connection. Maybe a neighbor or a friend of the family.”

We let our hopes run wild, envisioning a wise museum curator with a vast, lovingly preserved collection of Kindells, or maybe a bespectacled librarian whose meticulously organized files would be overflowing with heretofore unknown biographical details. We imagined that we’d feel a deep connection to Kindell just from standing on her street, walking through her town, and looking out at the same stretch of ocean that she would have seen when she was working on her pottery. Most of the outside world might have forgotten her, but surely there’d be someone in her hometown who would remember.

You know what’s coming: None of the people we talked to at the museum, the library, or the historical society had heard of Kindell. We were able to dig up some addresses and numbers from old phone books, and we found her listed as a participating artist in programs for the Laguna Beach Pageant of the Masters, an annual art festival that started in 1932. Other than that, it was as if Kindell were a ghost. Even when we saw the two story Spanish-style building that used to be Kindell’s studio – it was now home to a flooring company – we couldn’t muster any joy. We were so close, it was hard to admit we were coming up empty.

Back in Los Angeles, a search of the newspaper archive at the L.A. Public Library yielded a 1937 photo of Dorothy Kindell and two of her three young children participating in Laguna’s Pageant of the Masters. They were in 17th-century Dutch costume, posed in an imitation of a painting called Grace Before Meat by Jan Steen. The names in the photo caption also appeared on a genealogy Web site I came across.

What I’d found was the family tree of an 82-year-old woman named June Kindell Applegate. Suddenly with a few clicks, the barest outlines of Dorothy Kindell’s life were revealed.

Dorothy was born Dorothy Mae Pemberton on April 5, 1909, in Whittier, California. In 1926, she married William Marion Kindell in Hemet, and a year later their first child, June Pauline Kindell, was born in Laguna Beach. Her sister, Phyllis Darlene Kindell, was born two years later. Dorothy gave birth to a third child, William Jr., known as Billy, in 1933. She wound up dying less than three decades later, in 1961, in Redmond, Oregon. By then her husband and Billy were dead as well, leaving only her two daughters behind. June had listed her address and phone number in Port St. Lucie, Florida, on the genealogy Website. I wrote them down on a pad on my desk. Then I stared at them for several days.

I can think of few things I hate more than being cold-called by random people I don’t know, so I dreaded the thought of becoming a random caller. I dialed June anyway. As I introduced myself, I was nervous, talking a mile a minute, fearing she might hang up on me. When I finished, there was a long silence on the other end of the line.

“This is really a lot to take in,” she told me. I asked if I could telephone her again, once she’d had a chance to think. There was another long silence before June gave me a time to call her back.

The next weekend, on the appointed day, I went over to Jane’s and we sat around drinking coffee and honing a list of questions for June. But when June answered the phone, she had some questions of her own.

“Are you the same Christa Faust I found on Amazon?” she asked. “The crime writer?” I was. “Why are you doing this?” she wanted to know. I explained my admiration for Kindell pottery and my confusion over why her mother had not been more celebrated as an artist. June seemed satisfied, but she refused to allow me to record our conversation and didn’t want to answer any in-depth questions. I asked if she’d be willing to e-mail me answers. She agreed and told me that she’d pass my number along to Kindell’s grand daughter Kathe Nielsen, who was working on a catalog of Kindell pottery.

I e-mailed June my questions. No reply. So a few days later I called a third time. Turns out she had lost my e-mail message. But there was more to it than that: Answering questions about her mother was overwhelming, June told me, though she didn’t say why. Was she wary of letting someone else describe her mother’s work? Was she worried that I would characterize the subject matter in a prurient way? All June said was that she didn’t feel up to it. A week later my phone rang, a Florida number on the display. “It’s June Applegate,” she said. “Have you got a minute?”

Dorothy Kindell’s most active years as an artist were during World War II, which put her smack in the middle of the era best known for Varga Girls and morale-boosting USO cuties. Like Rosie the Riveter, the image of can-do womanhood that was popular at the time, Dorothy went to work out of necessity. Her husband was a plumber whose bum leg had kept him out of the military. Because the materials needed for his plumbing business were diverted to the war effort, the family had to rely on Dorothy’s income. While William helped his wife with her business, fixing kilns and the like, the designs were all Dorothy’s.

June told me parts of this. Her 81-year-old sister, Phyllis, told me some, too. Phyllis’s daughter Kathe filled in a few gaps. I felt like Jane and I had hit the mother lode.

The picture that emerged of Dorothy was of a no-nonsense businesswoman. She attended weekly church services with her family, was a respected member of the community, and even had a credit card when it was almost unheard of for a woman to have a credit card in her own name.

Dorothy often joked that she started the ceramic studio “because June needed braces.” June, meanwhile, was at first uncomfortable with her mother’s subject matter. As a teenager, June told me, she expressed her embarrassment about the sexiest figures. Dorothy replied, “A woman’s body is completely natural and nothing to be ashamed of.”

Dorothy treated her workers, mostly women, in the studio like family and hosted Fourth of July parties for them every year. The business flourished, and Dorothy saved enough money to retire to a horse ranch. But she barely had a chance to enjoy retirement. Dorothy was diabetic in a time when there weren’t many options for treatment.

In 1961, a few years after closing her shop, Dorothy Kindell died. She was 52, the same age Jane is now. (Note: This article was originally published in 2010. I’m 53 now!)

The more I got to know Dorothy, the more I felt as if I’d pushed back the tousled hair and revealed the face beneath. It was a face l recognized, a face not so different from my own. She brought a soulful heart to her ceramics that transcended the pop culture idiom in which she worked. Dorothy had become a kind of muse to Jane and me. If Dorothy could be forgotten, so could any one of our pulp and pop culture heroes. So could Jane. So could I. Somehow by remembering her, we were protecting ourselves.

As our search came to an end, I realized I needed something more. Trawling on eBay, I found one of Dorothy’s large pitchers, its handle a dancing woman in the nude. There was a chip in the spout and a fine, repaired crack, but the woman’s body was perfect. In mint condition a piece like this would fetch upwards of $1,200, way beyond my budget. But this one I could afford. She appealed to me, this ceramic lady who’d seen better days but was still sexy. How great it would be to have my own small piece of Dorothy, I thought, to share that kind of tangible connection. I put in the only bid. And I won.